10 Jul Peregrine Comes to Roost

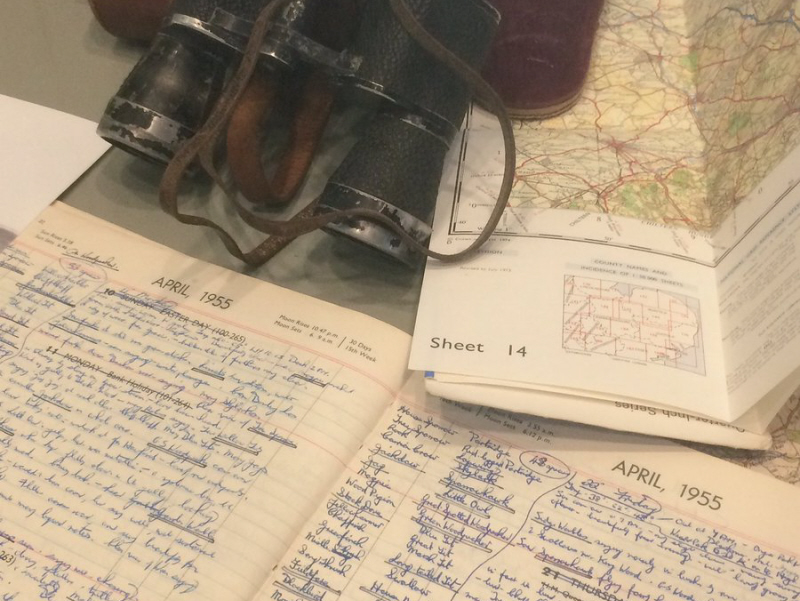

The papers and journals of J. A. Baker, the author of the 1967 nature writing book The Peregrine, have been given to the University of Essex Albert Sloman Library and this archive was launched at a meeting this week to discuss Baker’s life and work. In 2010 a new edition of The Peregrine was published, including Baker’s second book, The Hill of Summer. This introduced a classic of nature writing to a whole new audience who, while admiring the lyrical prose, have proved to be sceptical about Baker’s bird-watching skills and have queried whether he could possibly have seen so many peregrines and their kills. Also included in the 2010 edition were extracts from the diaries Baker had kept from the 1950s. Edited by ornithologist John Fanshawe, the diaries shed some light on this secretive man and his obsession with peregrines in his local patch. Mark Cocker and John Fanshawe, who both spoke at the archive launch, have tried to follow in Baker’s footsteps.

Born in Essex in 1926, John Alec Baker was an only child, living in Chelmsford for most of his life, walking, cycling and bird-watching. In the 1950s he worked for the Automobile Association, apparently giving this up to become a full-time writer. Baker appears to have had a difficult, lonely childhood and was affected by nervous depression. Hetty Saunders, who has catalogued the Baker collection, suggested that after his recovery from depression, doubt, dread and introspection were characteristic of his personality and his writing.

Head of Sociology, Professor Sean Nixon, set Baker’s writing in its historic context. He reminded listeners that, although the 2010 edition has created a seminal nature writing work admired by a younger generation of nature writers, it should not be forgotten that the book was published in 1967, in an era of post war writing that emphasised an observational culture. Bird-watching was encouraged as a recreational activity and sightings should be faithfully recorded in notebooks.

Mark Cocker challenged the accuracy of Baker’s observations suggesting that raptors are notoriously difficult to ‘get right’. He was particularly sceptical about observations such as Baker’s detailed account of peregrines bathing in a ford. Much of the technical information could have come from falconers. It was strange that Baker appears to have destroyed or manipulated much of the information on which the book is based. Did Baker wish to be an enigma? The debate centred around the truth of the peregrine observations and largely ignored the second book, The Hill of Summer, as well as any reflection or analysis on the literary craft employed in the writing of the books.

Despite spending ten years following the peregrine, Baker chose to focus on just one winter: “In my diary of a single winter…everything I describe took place while I was watching it”. It is clear when looking at the journal entry dates, and the weather observations, that the single winter must be the 1962-3 winter. The dates of the commencement of snow: “27 December – Snow lay thick in South Wood,” to the end of the longest winter: “5 March – The snow is neolithic, eroded by the warm south wind,” tally. Meteorological records show that snow began on 26-27 December; that January 1963 was the coldest month of the 20th century and that 6 March 1963 was the first day without frost anywhere in Britain. It was a winter difficult to forget if you lived through it, characterised by intense cold. There were losses of birds throughout the winter and records show that enormous flocks of wood-pigeon were recorded during January and February, with very big movements noted in early January and high mortality. Would peregrines have behaved differently in this exceptional winter?

The creation and cataloguing of the Baker archive will enable future research. Given permanently to the library by Baker’s brother-in-law, Bernard Coe, and John Fanshawe, the archive includes Baker’s letters, early manuscripts of The Peregrine, Baker’s ornithological diaries and some of his unpublished, early work.

From the interest of nature writers, falconers and PhD students at the launch, one might take Baker’s own words with a twist: “For ten years we followed him.” There will be more analysis to come.

The catalogue for the J. A. Baker Archive at the Albert Sloman Library can be found online:

http://libwww.essex.ac.uk/Archives/JABAKERARCHIVE.pdf

The University of Essex filmed a short video about the launch event here: